Team Amani Creating Opportunities

Doing things differently and opening new paths

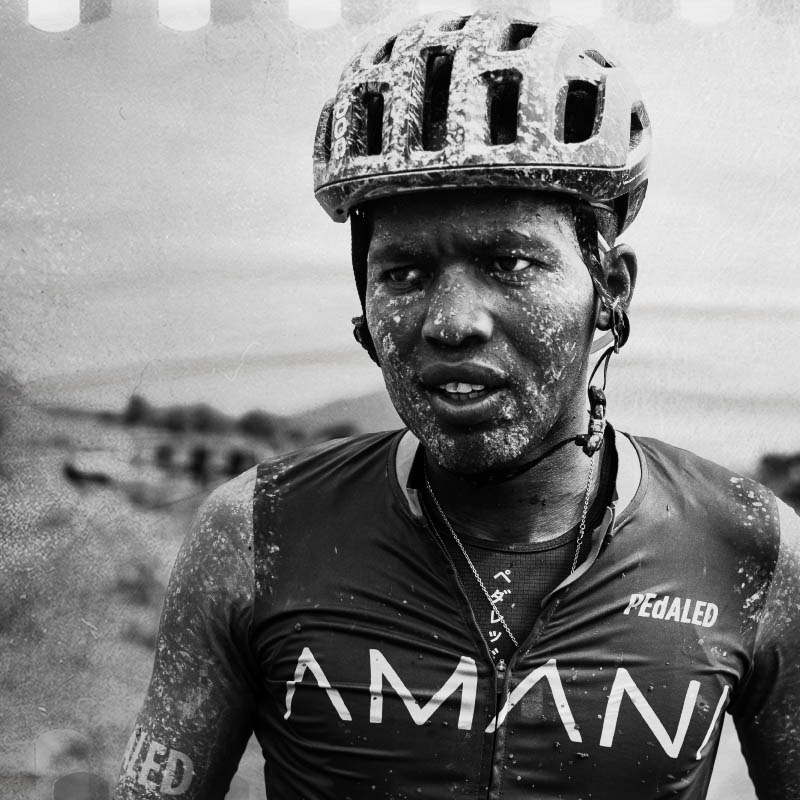

The 2022 season offered Factor-sponsored Team Amani a lot of success as well as profound loss. As the first year racing on Factor bikes, the team’s year was highlighted by victories at the Migration Gravel Race (in Kenya) and Evolution Gravel (in Tanzania) against a strong international field. At Cape Epic, their team took 4th in the Mixed competition. They also impressed a strong field in the US by taking 1st and 3rd at Vermont Overland. At the 2nd at Race Around Rwanda they grabbed 2nd, then 2nd at Rwanda Epic, and First (pairs) competition at Atlas Mountain Race.

“It was the first year that we had the same level of equipment as everyone else. Just the year before, we didn’t have a bike sponsor and our bikes failed all the time,” Team Amani co-founder Mikel Delagrange explained. “Then just bringing Factor aboard went a long way to leveling the playing field. We went from getting marginal results because we were never sure whether our bikes would make it to the line, to then winning those same races the next year.”

Finding unity in tragedy

Team Amani and all its sponsors suffered great loss in 2022 as well, with the tragic death of team founder and captain, Sule Kangangi. On August 27, 2022, Kangangi died as a result of injuries he sustained in a bike crash during the Vermont Overland gravel race. Having been instrumental in the founding of the team and a prominent role model for East African cyclists, it was a huge blow to more than just the team.

Fellow Amani member Anthony Koine agreed: “We all feel his absence, but the team has had to push on, press on because that’s what he would have wanted for us. It’s not easy, but we just have to do it with the same energy.”

Amani Performance Center

With the desire and commitment to carry Sule’s dream forward, Team Amani are building the Amani Performance Center based in Iten, Kenya. At an elevation of 2400m, it’s a town with a professional sports culture that has nurtured generations of exceptional long distance runners. “We’re building a facility for cycling there. We’re pretty far down the road. We’ve bought the land and the pump track and we’re building the athlete house. But we need a little more money so that we can finish the job,” Delagrange explained.

Building Amani Performance Center in Iten, Kenya, is no accident. “Since it sits 2400 meters above sea level, they clearly have some cardiovascular benefits, but I think it’s not too far-fetched for the parents of these kids to think, well, yes, sport is a path out of poverty. They’ve seen it with running. Now it’s just a different sport. We’re starting there and hopefully we can expand out,” said Delagrange.

Leveling the playing field

“We want to find the next generation. We want to give them the opportunities that our current class didn’t have,” Delagrange said. There is no question that the talent pool in East Africa is deep. The issue more seems to be alerting them to the opportunities a life in cycling can offer.

“One thing that has really resonated with us, Lachlan Morton is a key partner of our project. But he straddles two projects, going back and forth between ours and Esteban Chaves’ Foundation in Colombia,” Delagrange explained. “And they more or less have been in existence the same amount of time as us, they more or less have the same resources, but in three years, they have put three riders in the WorldTour. There are a lot of differences between Colombia and East Africa. Colombia has had a cycling culture since the 1970s. It’s the number two sport in the country. So, there is a fan base and an industry. But I would argue that the most compelling thing that has come out of this comparison for us is that Esteban and his brother have 700 riders to choose from for a 12-person team.”

Contrast that with the Amani Project in East Africa. “We have, across three countries, maybe 35. For us the challenge is clear. We’re just going to throw that net out and extend these opportunities for that next generation to be able to play this game. And when we have 700 riders to choose from, that’s going to be the moment where we can start offering the same level of competition, putting the same caliber of athlete forward for things like the WorldTour. That’s where we are putting all our investment and all our energy right now.”

Highlighting opportunities for women

Since thinking of cycling and in particular gravel racing as a career is still relatively new in East Africa, it can make finding women riders even more difficult. “When we first started, we thought finding women willing to participate would be a bigger challenge than it actually has been,” Delagrange said.

Taking a human approach

Oftentimes, there is little doubt in the athletic ability of the riders from East Africa, but other barriers prevent them from taking the next step in terms of international opportunities. “We are currently opening an initiative in Rwanda. It’s a little more modest at the moment. We are calling it The Spoke Academy and it’s about equipping Rwandan athletes with the professional skills they need,” Delagrange explained. “These are already established professional cyclists who need professional skills to be marketable to take that next step. Because Rwandans have this reputation for being fantastic athletes, but unable to speak either French or English.”

Though European teams might be aware of the huge talent an individual from Rwanda might have, they are unwilling to take the rider on-board. “Because they don’t have the linguistic abilities, they haven’t had that real life experience of how to get on a tram, how to travel on a plane, how to open a bank account. All these things which have actually worked against them because teams will go, oh well you can’t just hire one Rwandan, you have to hire a whole coterie of support staff, and so they’re not worth it, right,” Delagrange continued.

“So what we’re trying to do now with this academy, which is run by one of our Rwandan partners, is try to give them these life skills. They don’t even have to be a part of our team, we don’t care. It’s for anybody who is serious about becoming a professional cyclist; we tell them to come here, get what they need and then hopefully we can start undermining that stereotype of Africans not being hirable on the international stage.”

Using gravel to grow

Not only have Delagrange and members of the Amani Project founded the team, they have also established two extremely compelling and successful gravel races in East Africa, the Migration Gravel Race in Kenya and Evolution Gravel in Tanzania. These races have drawn some of the top male and female gravel racers from around the world and give Team Amani and other African riders the chance to showcase their talents and learn from the international field.

“For me and Sule, it was clear that road cycling was not an option right now. The infrastructure is such and the mindset of the powers that be is such that I don’t see any viable path forward for East Africans, at least at the moment. But that doesn’t mean that we can’t get in by the back door,” Delagrange explained. “For us, riding off-road plays to our strengths because we have access to a lot of gravel roads! Rather than trying to force a square peg into a round hole. We’re just trying to do things differently and see if it resonates.”

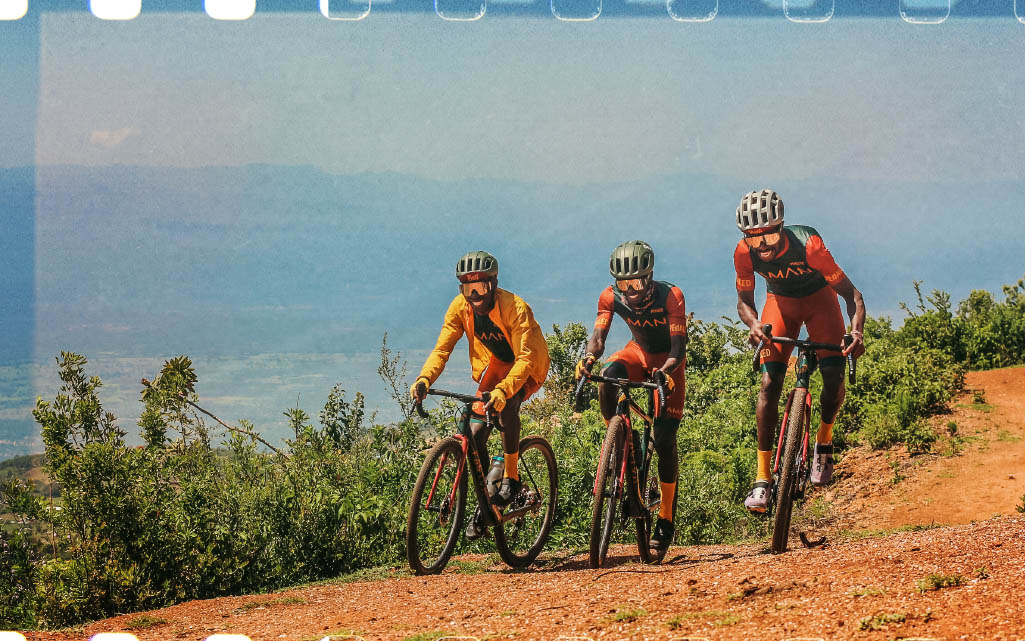

An OSTRO Gravel inspired by East Africa

Team Amani earned their best results in 2022 on the Factor LS in gravel and the LANDO in mountain bike events like the Cape Epic. For 2023, a very special OSTRO Gravel has been prepared for the team to help them reach even bigger goals. “The core colors are the colors of the team. And those colors are also key primary East African colors. That maroon color is actually called Nairobi Red, and then the green is a primary color from East African flags,” Delagrange said. “I believe the Migration Race and various other things played into touches like the fork, which is really nice.”

Jay Gundizk, Factor’s Creative Director, explained his thought process behind his design for the frame:

“I based the Amani OSTRO Gravel design on the colors found in the landscapes of the Rift Valley in Kenya and plays off the Team Amani kit colors for 2023. The stylized print for the forks contrasts the main body colors and is based on a Cheetah print pattern. Cheetahs are found throughout the Maasai Mara National Reserve, Rift Valley Province in Kenya and are a true symbol of speed and athleticism, not unlike the riders on Team Amani. The design is playfully bold and represents the spirit of the East African riders.”

Plans for 2023

With an ever-growing gravel calendar, in Africa as well as in North America and Europe, the number of objectives and opportunities grow as well. The 2023 season promises to be a big year for the team. “We’re sending a team to Cape Epic next. It’ll be a very competitive team, so we are looking forward to that. And then we have a number of riders doing an American campaign that will start with Sea Otter and then go all the way to Unbound,” Delagrange revealed.

“There’ll be a lot of American racing early in the season, and even for Unbound, we have some guys targeting the Unbound XL and we think we have a good chance of doing very well at that one. And then we come back to Africa for our own races where we have a big international field coming again, so that’s really exciting. And hopefully we’ll do well on our own home turf, and then we will go for the Gravel Earth Series, which the Migration Gravel Race is part of, but also these big races like the Rift and others.”

With a stacked schedule like that, the riders of the Team Amani will have an excellent opportunity to get the most out of their customized OSTRO Gravel bikes.

Order your own OSTRO Gravel Amani Edition

We are so excited about Team Amani and the OG Amani Edition that we are making it available for purchase for a limited time. And 10% of all proceeds from the sale of the bike will go towards the gofundme for Team Amani, which is currently building the Amani Performance Center based in Iten, Kenya. It will be a facility where the next generation of East African athletes can be nurtured for success in the sport. They have the land, have built the pump track, and now just need some help to finish building the house.

© 2026 Factor Bikes. All rights reserved / Privacy Policy |Terms