The Aerodynamic Story

The thoughts behind the numbers

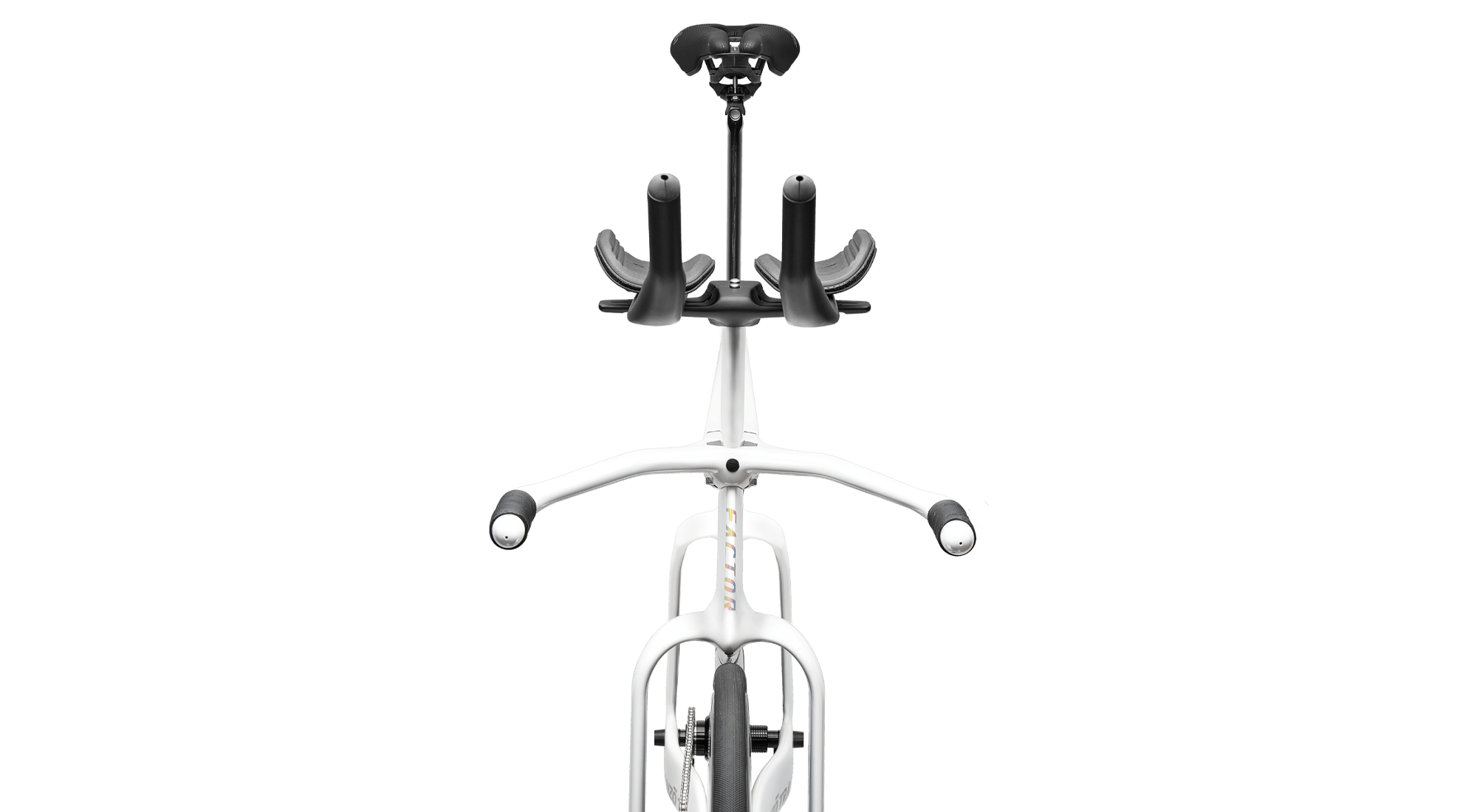

There are times when a bike brand needs to be bold. In research and development. In design, production, and promotion. For Factor, that has definitely been true with our most recent release, the ONE.

Though there is a lot of bold innovation to unpack with the release of the ONE, the most eye-catching, headline-generating aspect of the bike inevitably falls on its aerodynamics. “Aero is everything” has been a catch phrase in the cycling industry for many years. However, most people don’t really have a great grasp of what actually goes into making an aerodynamic bike. Until fairly recently, even engineers have been more or less relying on antiquated understandings of fluid dynamics when designing bikes. Think back to how bikes looked just a decade ago.

In the development of the ONE, Factor’s engineers and designers led by Chief Engineer, Graham Shrive, have taken input from multiple external sources, from the UCI rule book as well as suggestions from our athletes. They then combined those points with advances in available CFD systems as well as their own accumulated knowledge and experience, with the ONE being the end result.

Though the engineers had long had the ambition to update the original Factor ONE, it was really Alex Dowsett’s request for a “leadout bike” in the ilk of a HANZŌ with drop bars that acted as the crystalising catalyst that accelerated work on the new ONE.

Read the rulebook

Though it’s fashionable, and sometimes fun, to rail against the UCI and their rulebook, Factor’s engineers see the official design parameters as an opportunity to develop something special. Keeping an eye on the sometimes subtle changes to the rules can frequently be the key to radical advancements in frame design. Such a change proved as much during the development of the ONE.

In 2024, UCI rules were subtly modified to allow the down tube box to cover a part of the fork, whereas previously the entire fork needed to be inside the fork box. This change is so recent that it was not even available to our engineers during the design of the HANZŌ Track.

“It’s a really subtle but important change to the UCI rules around the fork box and down tube box that has really had a big impact on how we designed the ONE’s fork and down tube, and what we are doing with the aerodynamics. That’s what unlocked this whole forward-set fork design while still being able to do it with a pretty deep fork leg,” Graham explained.

“So you really have to be open and alert to these subtle small changes to the UCI rules, and you have to be open minded about how these small changes can influence what you are able to do with the bike.”

Aero toolkit

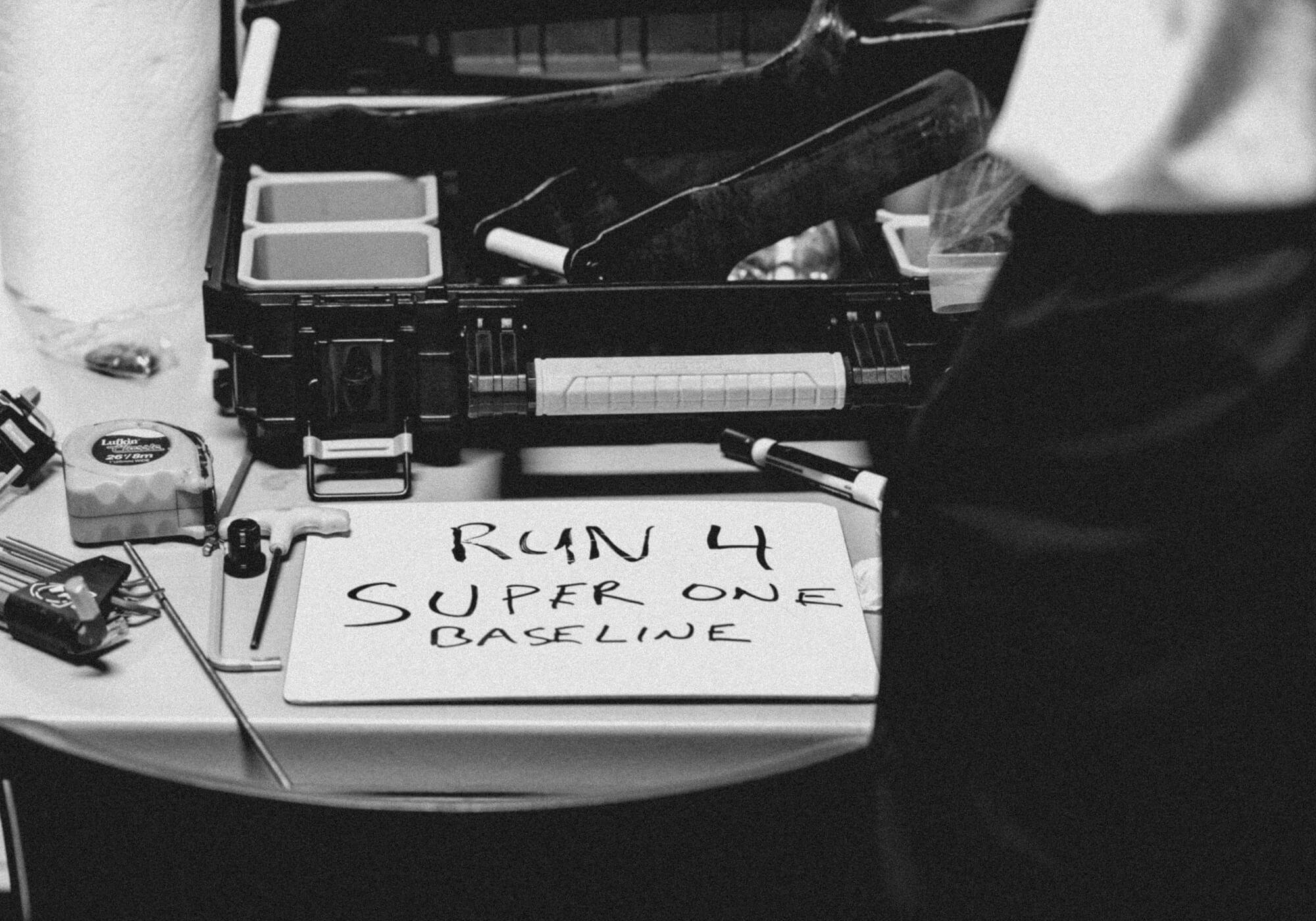

From conception to production took about a year for the ONE. The team of engineers based in Canada were able to take advantage not only of the world class wind tunnel facilities in Guelph, but also advanced and ever-improving CFD systems. That combo makes the iteration process much more manageable. But sometimes, Graham would still have to sleep on his studio floor for three nights ahead of a wind tunnel appointment to ensure everything would be ready and run seamlessly.

“We call it our aero toolkit, and that is a progression of steps in the design process. The first thing to understand with CFD is that it is a visualisation tool. Visualisation of aerodynamics is one of the most challenging things you can do,” Graham explained. “Companies literally use smoke and mirrors in the wind tunnel to try to see what the wind will do. A lot of progress is being made in that area, but it is still very imprecise in a wind tunnel.”

Learning the true behaviour of airflow around a bicycle with and without a rider is essentially the holy grail for all bike brands, and proves to be the hardest phenomenon to quantify. “Captialising on a more comprehensive understanding of flow structure is where the ONE comes from. We’re trying to visualise that airflow, which allows us to make meaningful change,” Graham said.

“With CFD, what we are trying to determine is what the airflow is doing, and more importantly, what can we do that makes a meaningful change to the behaviour of that airflow. And this is what’s really exciting with CFD right now, every month our CFD partner is adding new parameters. For instance, they recently added a very compelling visualisation of the stagnation pressure which allows us to examine the flow structure, giving us a new insight into not just how the static pressure changes, but also how and where flow will stall and start to shed vortices. That’s something we were never able to visualise before.”

The process of refinement was incredibly intensive, with hundreds of virtual models prepared, with simulated environments in CFD, and studied extensively until the engineer team found the best combination of features and shapes. The cumulative improvement discovered by the agglomeration of these small changes led to the revolutionary advancement of the system as a whole.

“The process usually starts with early sketching, thinking, looking at it, asking ourselves, is this a good idea, does it look good? We’ll sketch all ideas, then put it into the computer, and validate it in CFD,” Graham confirmed. “In CFD, we’ll look at the effect, the effect on the wheel, the effect on the down tube, and the effect on the rider’s legs. So we are looking at all these aspects and trying to pull it apart and understand what’s happening with that airflow.”

The iterative design process builds on our previous knowledge and allows the team to select the best option that will result in the best bike for the rider and the purpose. Good ideas don’t die, they just sometimes live on in a different form, on a different future bike. In addition to finding the best solution in developing an aerodynamic bike, it is important to pay attention to the form in addition to the function.

“If you ignore the rider's perception, a lot of times you’ll get a really ugly bike. Making sure the bike is visually compelling is also a really big part of the design process,” Graham said. “Our industrial designer’s whole job is to try to make it look elegant. The ONE could look like a beastly nightmare; we have all seen many examples of bikes that focused only on pure engineering. These are clearly very functional bikes, but aesthetically…you have to be a certain kind of rider to choose a bike that looks like that. In our minds, a bike still has to look attractive or compelling. You want the rider to be able to feel passionate about it.”

Wind tunnel testing

There is not a bike in the WorldTour today that has not been tested in the wind tunnel before being released. But for most brands, their time in the wind tunnel comes at the end of the design process; as a way to validate, hopefully, the design decisions made in the development process. But by then, it would be virtually impossible for the brand to make any changes. The bike design is set in stone, or more to the point, an expensive carbon layup.

For Factor, owning its own factory proves to be a huge advantage since we have total control over everything from tooling to layup scheduling and everything in between. That means that we can prototype full frames or frame sections to take into the wind tunnel well before designs have been finalised. It’s truly a validation phase that can result in a total re-evaluation of the design.

“We definitely spend a lot of time in the wind tunnel. The stress and effort that go into it, everybody laughs at me, but I’ll sleep on my workshop floor for a couple of days before we’re going into the wind tunnel because I’ll be running three 3D printers simultaneously, you have to be there to clear the bed to start the next print to keep everything on track, because you are always trying to fit more and more and more into your time in the wind tunnel,” Graham revealed.

“We had a lot of requests from riders a year or two ago which was basically for a HANZŌ with road bars. Using the wind tunnel, we can go in with 3D printed things or we’ll use what we call mule bikes, which are frames that can receive a variety of tube shapes on a structural backbone, allowing us to take the swap in different head tubes, seat tubes, downtubes, forks or whatever, and we can test a crazy number of setups to find what is working.”

The main challenge for going into the wind tunnel is that it is time consuming and it’s expensive. But it is the final word on performance. And everything is real. The wheels are spinning, the spokes are there. “All the things that computationally in some cases would take us forever to simulate, you can just throw it in the wind tunnel and test it,” Graham explained. “We did a lot of tests last year on different tire sizes, spoke configurations and shapes, different treads and textures, attempting to determine what these do to downstream airflow. That’s not something that is available to simulate yet. Trying to simulate a textured tire takes more computational power than the whole rest of the bike does.”

With CFD still a developing science, the inevitability of needing to go into the wind tunnel to have the last word on a design’s airflow performance means that it is extremely useful to have strong ties to a world class wind tunnel, like RWDI in Guelph, Ontario, Canada.

“We go to multiple tunnels, but our usual facility is in Guelph, Canada. I’ve been working with them for over 10 years. They specialise in buildings and bridge aerodynamics. So we’re always having to book 6, 8, 10 months in advance,” Graham explained. “We’re not their primary business, but the level of technical expertise is world class. There are a lot of other cool wind tunnels becoming available, like SASI in Australia, Silverstone in the UK, and several others. We are hoping to see a proliferation of sports-only wind tunnels, but for now, you can’t beat Guelph’s level as a wind tunnel partner.”

The graphs behind the numbers

When we go into the wind tunnel, we run tests intended to repeat as accurately as possible the specific experiments that we have already tested virtually in CFD. When undertaking aerodynamic testing, consistency, diligence, and commitment to continuity and attention to detail make the difference between a marketing exercise, and a useful investigation into aerodynamic performance gains.

When testing in a wind tunnel, it's important to understand several terms that are frequently used in describing aerodynamic performance. The most basic of which is the yaw sweep, which represents the relative angle of the wind to the riders direction of travel. For example, riding in a cross wind exemplifies the effects seen at these higher yaw angles.

In the case of this graph below, the X-axis indicates the degree of airflow yaw to the direction of travel while the Y-axis indicates the grams in drag generated at 48km/h or 30mph. At zero yaw, all bikes cluster around the same output requirement, but the ONE truly shows its pedigree once the yaw becomes more extreme. This is a significant advantage, especially since the wind is seldom coming directly head-on. Real-world challenges always appear in crosswinds, so if the bike actually assists with thrust as the winds become more unmanageable, the rider will feel the benefit and save energy. Although this graph shows the real values of the bike only tests done at RWDI, we have obfuscated the absolute values for competitive purposes. Third party tests are available that can provide further insight if one seeks them out.

As expected, the ONE out-performed the most recent OSTRO VAM, which had already out-performed most of our competitors in third-party testing. Our own wind tunnel tests confirmed those numbers. “It’s not totally a 1:1 comparison since the bikes were tested at different tunnel sessions, so inevitably there is a normalization process which can lead to small variables,” Graham explained. “But overall, what we see is that the curves are fairly similar. The SL8 and S5 do quite poorly at yaw versus the OSTRO.” And even less well against the ONE. These curve shapes match the published values for the bike-only observed by third-party testing done by Cyclingnews at Silverstone.

The percentages provided in the ONE launch documents (8% to the Ostro2, 15% to the 2024 S5, and 22% to the SL8) are based on the straight average of drag, across a +/- 15 degree yaw sweep. Although the magnitude of these differences is heavily dependent on the individual wind tunnel configuration, there is no doubt that the trends have been replicated independently by outside (unbiased) third parties. These bikes had the same AB02 handlebars (where possible) and standardised wheels and tyres, reflecting how riders would likely set their own bikes up. Many brands have engaged in creative spec choices and include things like extremely deep wheels, handlebars, and very small tires in their stock builds provided to third party magazines, distorting the actual apples to apples comparison.

We test our bikes as similarly spec’d as possible to how our riders are using them at the WorldTour, as we feel this is the truest representation of the real world. For example, testing one bike with 25 or 26mm tires, or even just tires that the wheels are optimized for can often make a greater difference than anything else a designer can realistically do with a frame. There has been much debate around testing with riders, with dummies, or with something in between. However, for the purposes of comparison, bike-only testing is the only way to isolate as many variables as possible, and thus are the values we share publicly as they are the only ones that are repeatable for a third party. We have our own protocols in-house which include moving/pedaling legs, half mannequins, and full dummies, which are used as internal development tools where appropriate. There is no one correct answer to the question of “how” to test, therefore we attempt to be as agnostic and repeatable as possible with our publically available data.

Exploiting the crosswind

The major fun in bicycle design comes when you feel you are really moving the needle, adding something to the general understanding of real-world performance, and helping your riders to excel, improve, and enjoy.

The ONE is a bold bike that makes bold claims. Not only in aerodynamics, but in geometry, handling, and aesthetics. It’s a package deal totally committed to making the rider faster, to helping athletes win races. That’s not the end of the story. Just the latest chapter. This is definitely a case of watch this space.

© 2026 Factor Bikes. All rights reserved / Privacy Policy |Terms