The Migration Diaries - David Millar joins Factor’s Rob Gitelis taking on the Migration Gravel Race

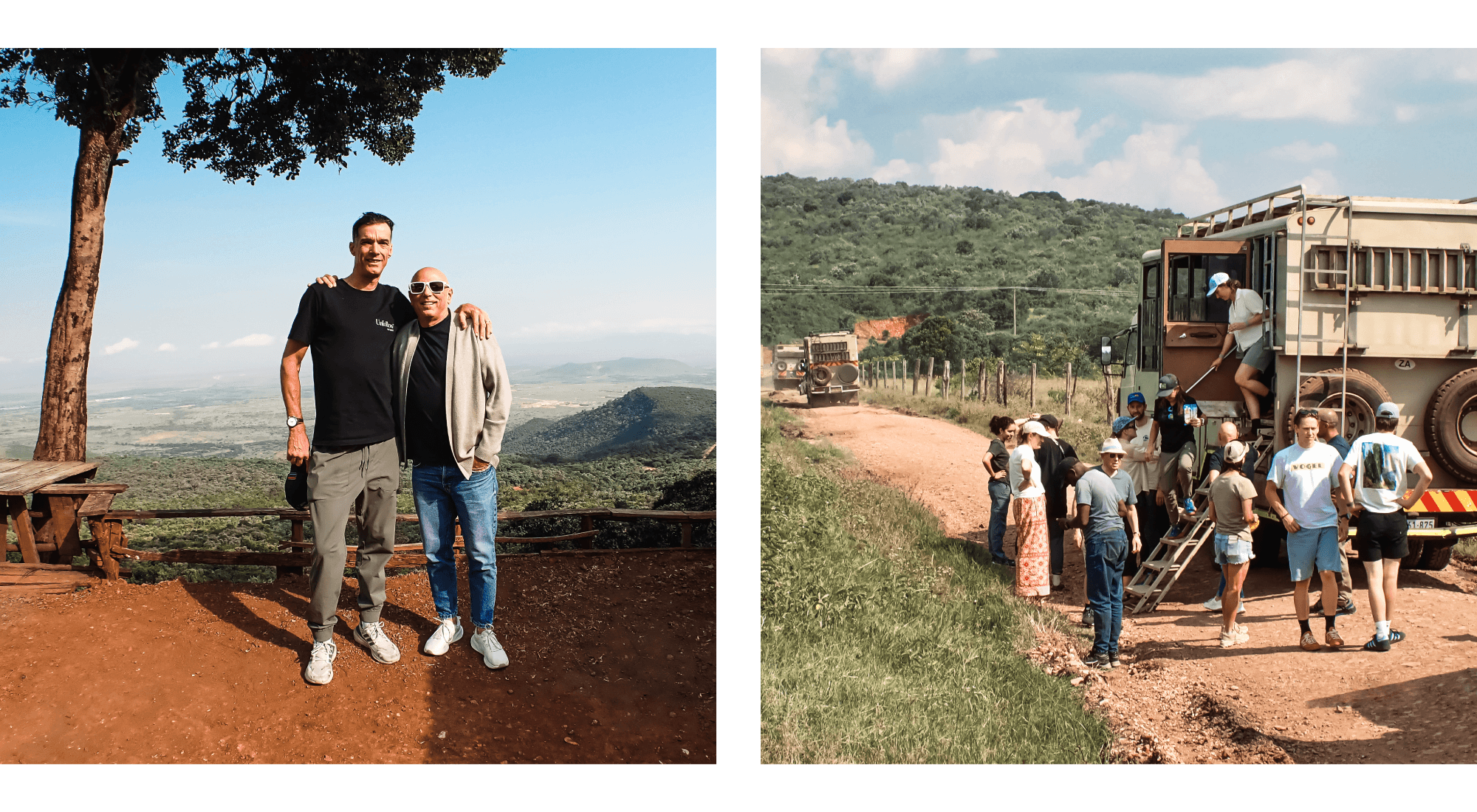

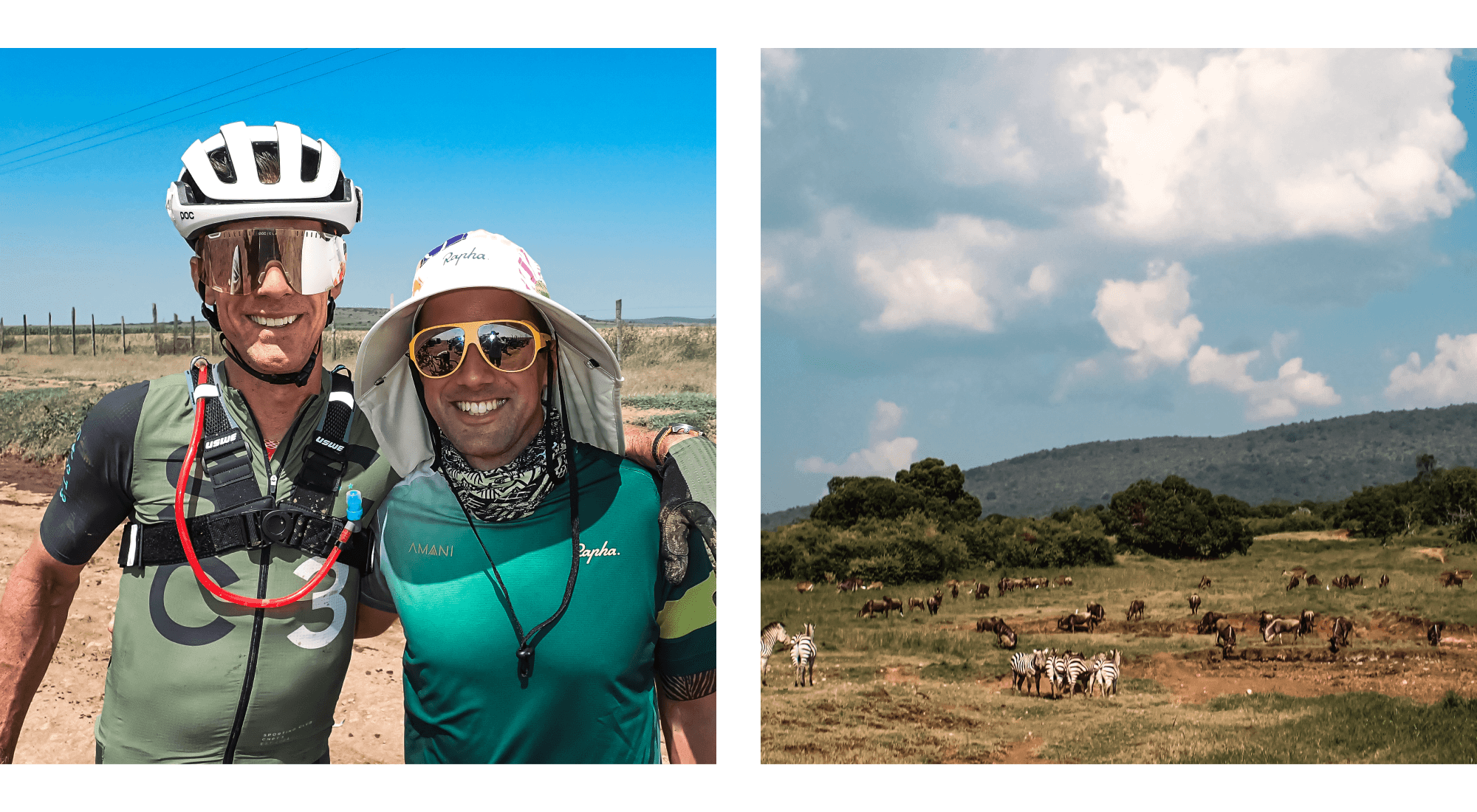

Fellow travelers soaking up the experience

In just its fourth edition, the Migration Gravel Race has become a hallmark event for international gravel racing. As a member of the prestigious Gravel Earth Series, Migration Gravel Race invites participants to test themselves riding across the Maasai Mara in Kenya, following the migration route of native wildebeests.

This is not your ordinary gravel race. It’s an opportunity to experience more than the spirit of competition or even the spirit of gravel. Anyone who has raced it before will tell you, it’s a life changing experience. As part of the Amani Project, the goal of the Migration Gravel Race is to encourage riders from all over the world to test themselves in East Africa.

David Millar will be sending us regular dispatches throughout the four stages, sharing some of what he and Rob will be facing.

Day 1 – Transferring to basecamp

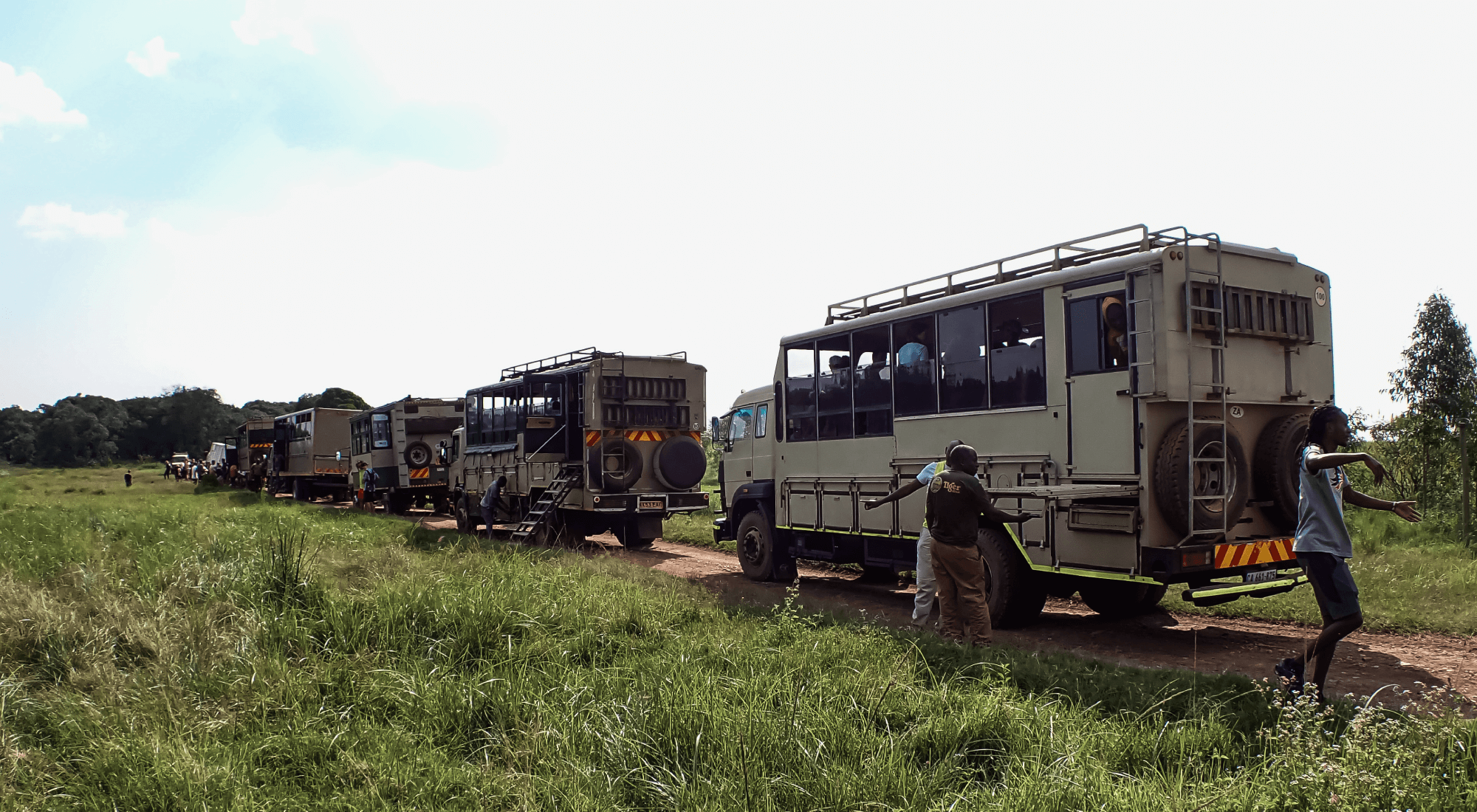

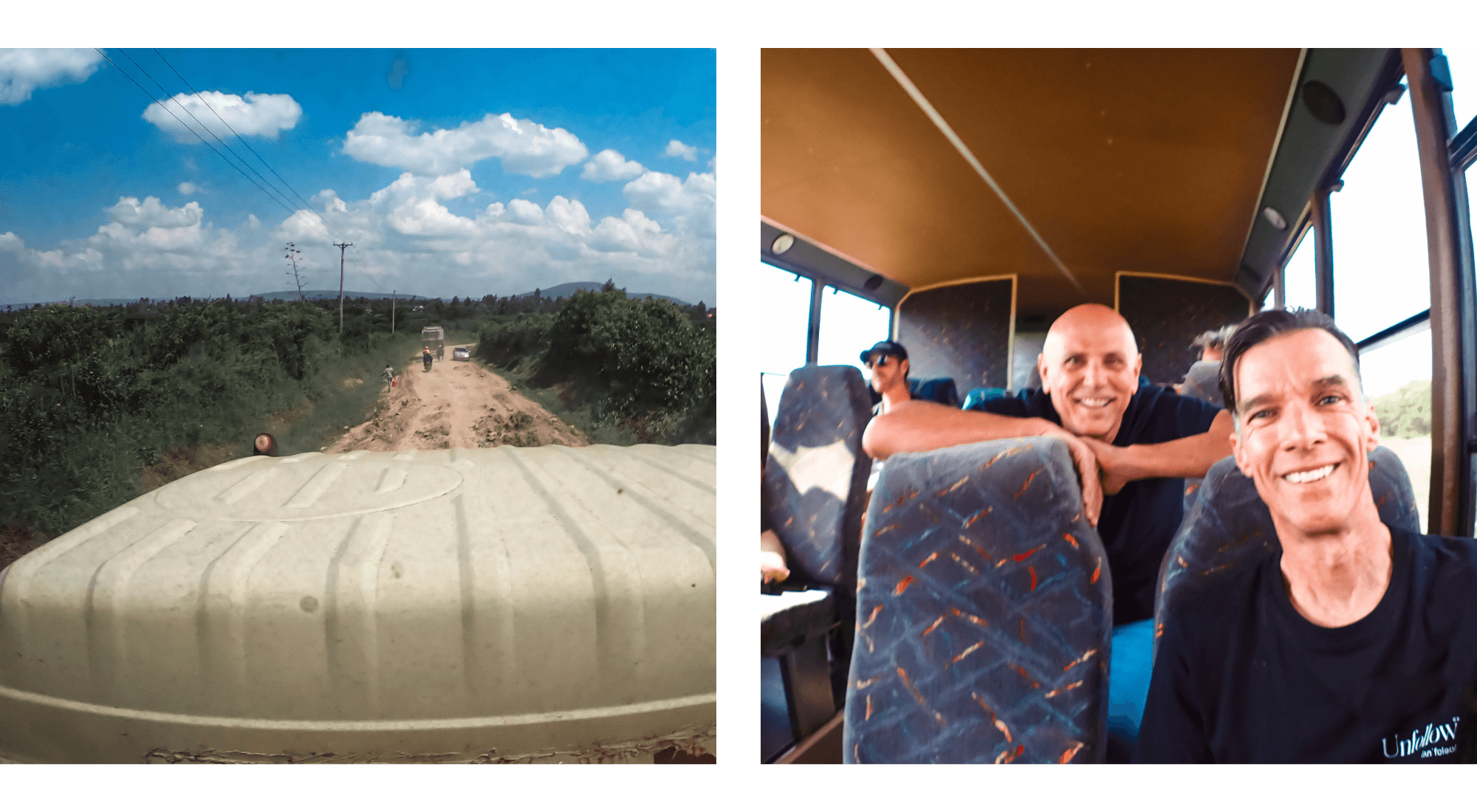

As I write this, I’m sitting on an overland bus. It's not your normal bus but a 4x4 raised truck with a safari-windowed 24-seat cabin. It means business and is an indication of what lies ahead. We’re setting off from Nairobi on a six-hour trip deep into the Kenyan bush to a place called the Mara, where the Migration Race will start.

Tomorrow it begins: 650 km and 8000 m of climbing over four days, tracking the migration journey of the wildebeest. From what I hear, it’s gravel on acid. This is the fourth edition, and it’s already become a mythical event. It’s part of the Amani project, created to give African riders a race of their own in their homeland, one that would bring the competition to them while also delivering an aspirational event for the local people and up-and-coming riders. Ultimately, that’s the mission of Amani: to offer a pathway for young Africans to enter the world of cycling.

Kenya is synonymous with distance running and endurance athletes, the exact physiological type suited to professional cycling. Yet cycling isn’t an option; the cost is more than prohibitive. It’s an impossible sport to even dream of for almost all young Africans. Amani wants to change that: through their foundation, their vision is to make the impossible possible, to make dreams a reality.

Photo credit: John Kasaian

Factor’s history with Amani

Beside me on the bus is Rob Gitelis, a good friend and founder of Factor Bikes and Black Inc. Being here and taking part was his idea. I got a message from him in December: “Let’s do the Migration Race.” So here we are.

Factor was one of the first cycling brands to support Team Amani, beginning three years ago. When I asked why, he said, “Because it was the right thing to do.” That kind of sums up how Rob makes decisions. He’s passionate about the project, on a par with the Tour de France. Different but the same, I’d go as far as to say it fills him with more pride and purpose.

Once upon a time, Rob was a pro bike racer. He stopped quite young, settled in Taiwan, and quickly became a one-man innovation machine in bike design and manufacturing, transferring his chemical engineering education into carbon fiber innovation. He ended up being the wizard behind the curtain for many of the most respected bike manufacturers. They’d go to Rob to solve their problems and make the bikes they didn’t know how to. Eventually, he got bored of this, and figured he could do it better on his own, and Factor was born.

Packing to be prepared for anything

We both arrived yesterday morning. Our first mission was unpacking and repacking. We’d both brought more than we needed out of fear of forgetting something important while knowing we’d have to decant into a smaller bag for the five days of camping. As I emptied out the mother load, I said to Rob, “Bet I’m the only person here with a cashmere jumper.” He replied from behind me, “What, one like this?” I turned around to see him holding out his own cashmere jumper. Good start.

I educated Rob on the Cape Epic method my sister had introduced me to of creating daily packs of clothing and nutrition. We methodically separated everything out, and I blew Rob’s mind with modern nutrition protocols. He cannot fathom the amount of fuel we’ll be taking on board.

Meeting fellow travelers

The bus trip continues. We just had our first stop on the ridge entering the Rift Valley. It’s spectacular. I got chatting with another traveler at the roadside. (I don’t feel we’re riders or racers here; traveler seems more appropriate.) He did the Migration Race last year. I asked how it was. “The most amazing experience of my life,” he said. I asked why. “It’s simply incredible: wildebeest running next to you, elephants crossing in front…” He was racing, yet he quickly understood it was so much more than a race.

Which is good, because I’m not here to race. Rob and I are here for the experience. We want to have the bandwidth to appreciate and absorb everything that happens. Make moments, create a peak experience that will stay with us. This is Rob’s primary motivation for coming. He says he’s put too many things off, always said next year. He realizes now that next year never comes. We’ve just got now.

We're doing it in style. We have all the gear, and even with my recent gravel exploits, we pretty much have no idea. I thought we were the most inexperienced here as everyone else is radiating the spirit of gravel. Fortunately, and surprisingly, I bumped into fellow travelers Chris McCormack (triathlete legend) and Nick Gates (former pro cyclist) at the hotel last night. They genuinely are clueless.

Chris is on a mountain bike that a sponsor gave him in 2012, never unboxed until he took it to the shop last week. Nick has a gravel bike but has never ridden it off-road and was shocked to hear that gravel tires are supposed to be run at approximately 25 psi versus the 80 psi he was riding. Neither has a bike computer, nor do they even own one. They learned that it’s quite important to have one, that we have maps to download and a route to follow. So they were frantically on their phones trying to download an app that would do the job for them.

It got better the more we asked them. They were unaware tubeless tires were de rigueur, that electric gears were reliable, and that bar-ends on a mountain bike went out of fashion in the 1990s. There are two route options: the Zebra being the shorter, the Leopard the longer. Chris and Nick are doing the Zebra with six others. They have a following car, and as I type this, two hours into our overland bus journey, they will be boarding a small plane in Nairobi to take the 45-minute flight to the Mara. In comparison to them, Rob and I are the embodiment of the spirit of gravel.

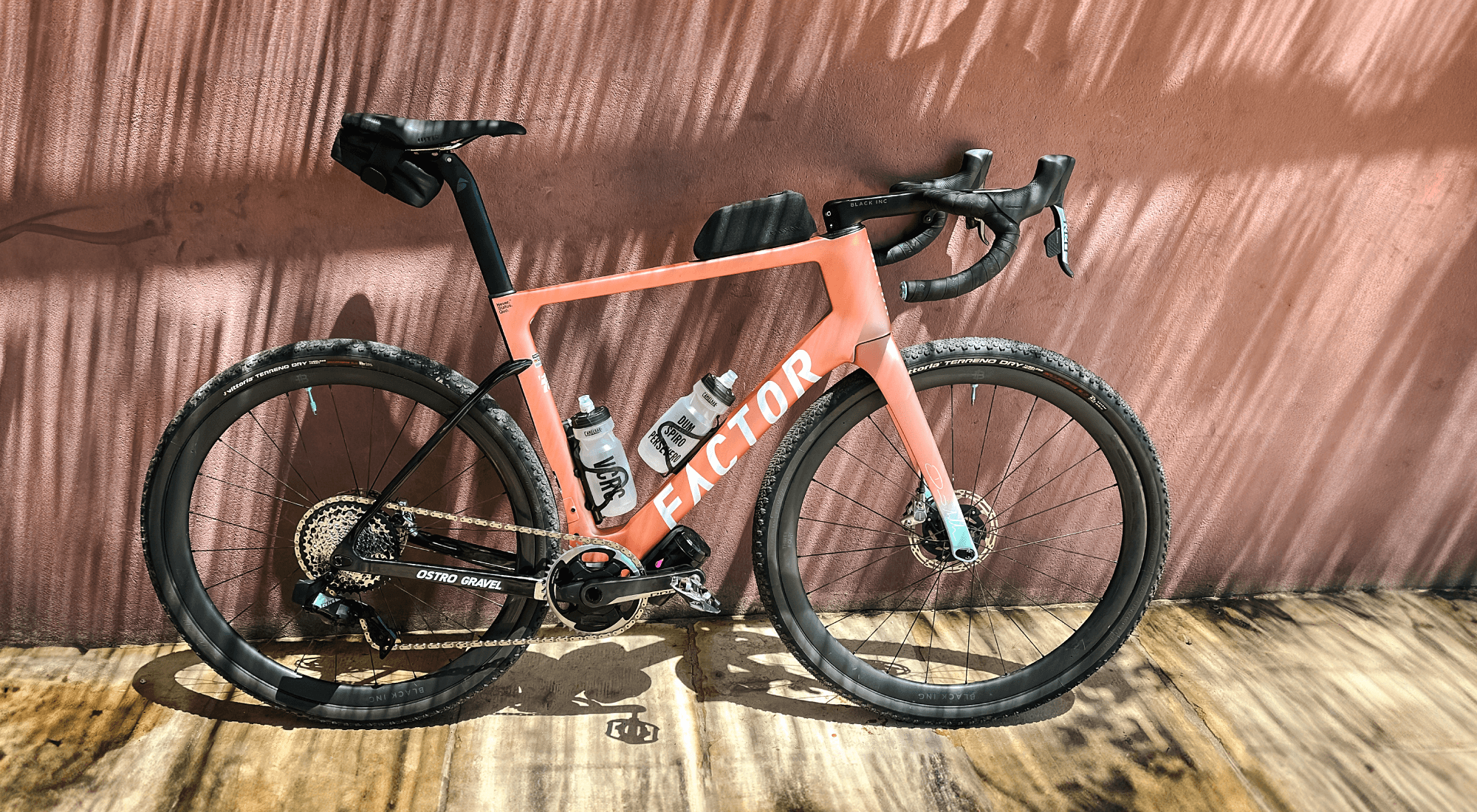

The right gear for the task

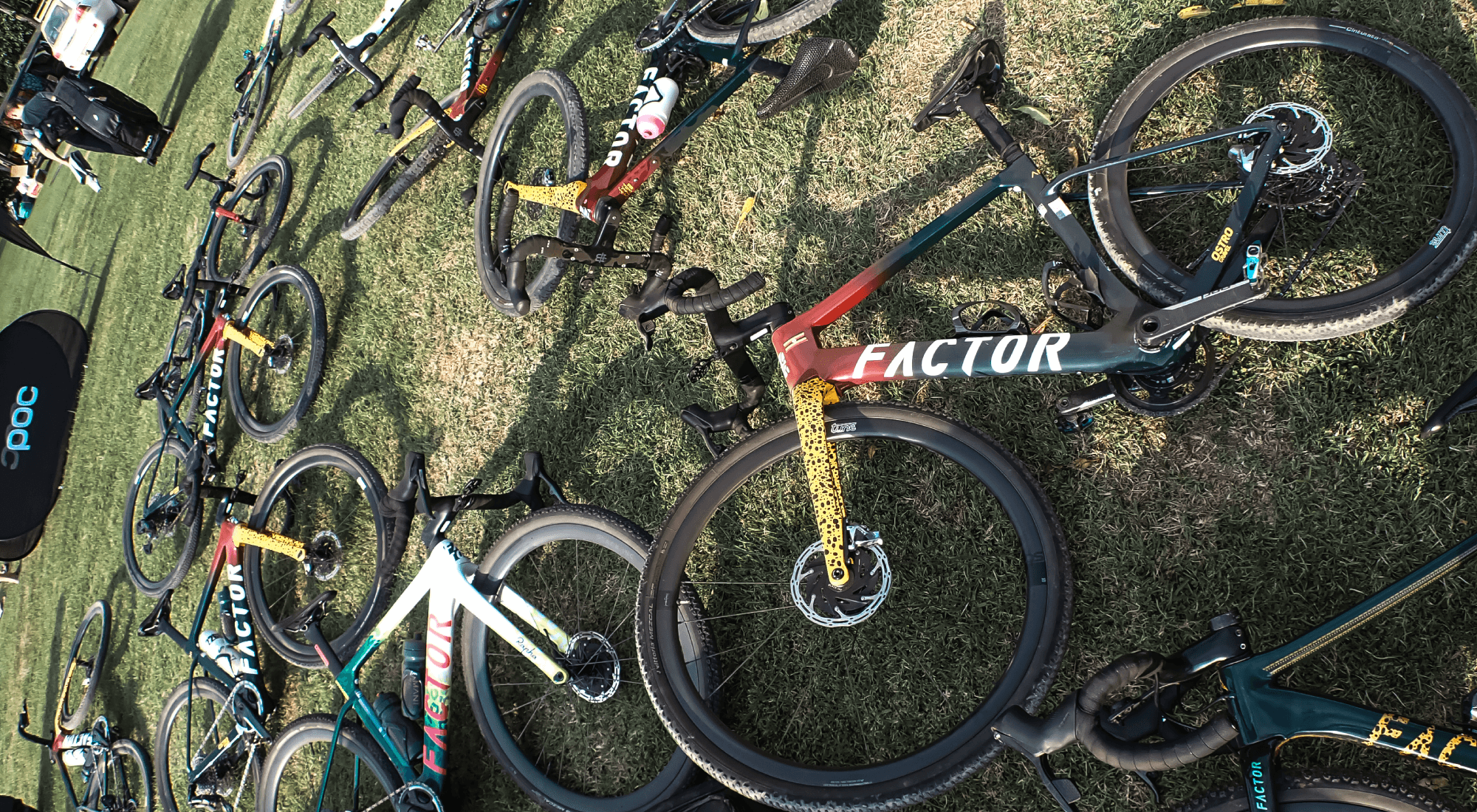

We're riding the Factor OSTRO Gravel, the lightest/fastest gravel bike out there, in a signature edition livery: rose gold with a hint of teal on the fork. Black Inc 34 bomb-proof gravel aero wheels with Schwalbe Overland 45 front and rear tires for Rob and Vittoria Terreno Dry 47 front and 45 rear for me, foam inserts for both of us. Contrary to Nick Gates, we’ll be riding approximately 25 psi. Black Inc Integrated Aero Barstem system with double roll bar tape. I'm using a WTB Ti Silverado saddle, same as my mountain bike as I'm prioritizing comfort. Rob is on a Selle Italia SLR 3D, maybe not so comfortable, but what he knows. SPD pedals for both of us. I’m using my MTB trail pedals which are a bit heavier but have a slightly bigger platform which I like as they feel a bit more roadie.

Saddlebag rescue pack, the OSTRO Gravel comes with extra mounts. I’ve fitted a top tube frame bag that bolts onto the frame, and I’m using the third bottle cage mount under the down tube to store a gilet and arm warmers, just in case. Muc-Off saddle bags with full rescue resources that somebody else will have to help us with. We’ll both be using USWE hydration packs to bring our water carrying up to 3 liters. As for apparel, we’ll be in the CHPT3 SCC3 shorts and jersey, a kit I designed to handle exactly this sort of event. Essentially a lightweight road aero kit with cargo pockets on the shorts. As for protection, we’re POC all the way, the gravel-specific OMNE helmet and face shield Devour glasses. We’re fully equipped for speed, and as ever, we haven’t sacrificed style, which is handy as we’re not going to be going fast.

Basecamp arrival, finally

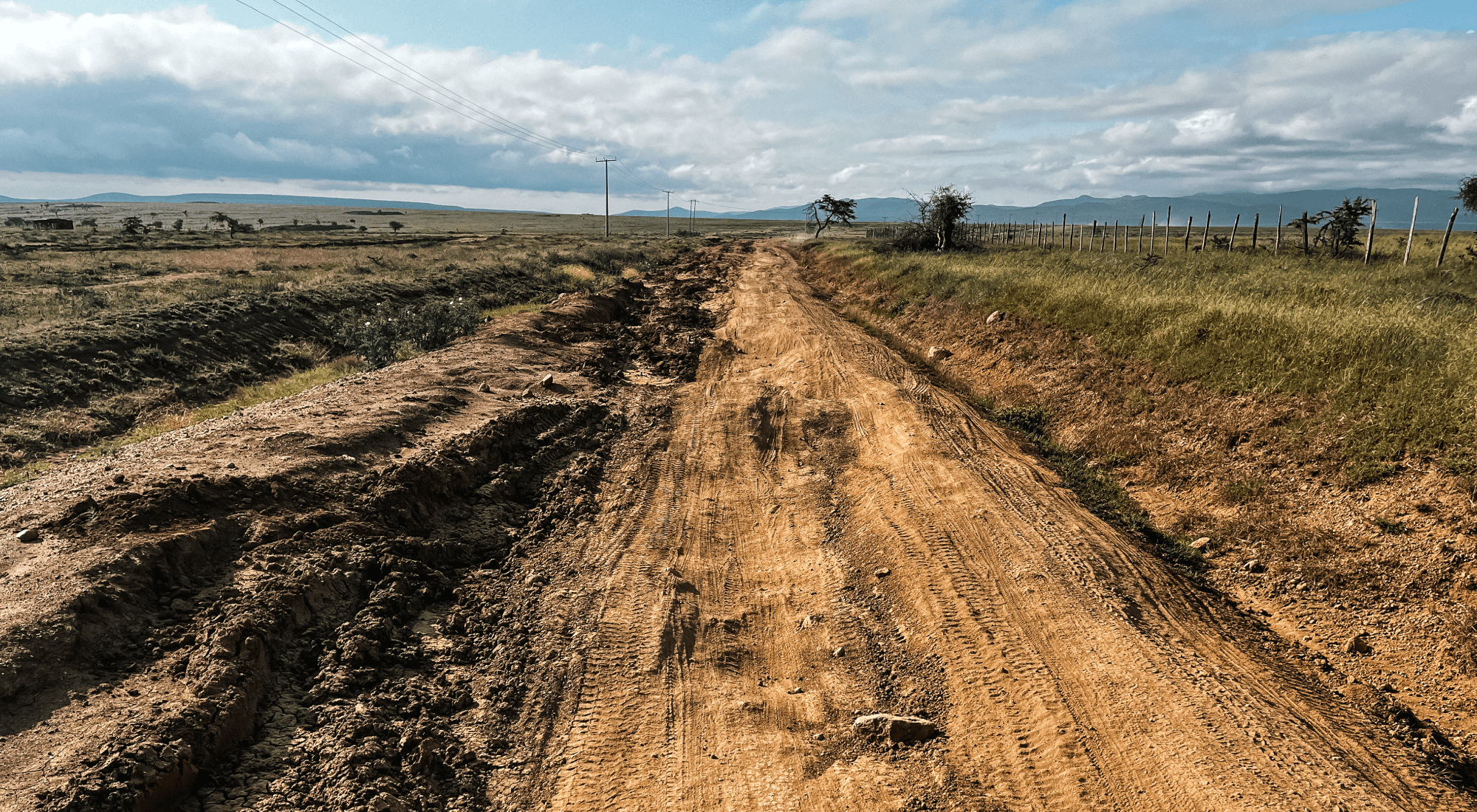

Right now we’re going very slow. We’ve been on the road for seven and a half hours, the last two and a half at a crawl on rain-damaged dirt roads. We’ve been stuck twice, seen baboons, zebras, and warthogs. Somebody asked if warthogs are dangerous. Rob knew, “I know most of my animals from the Lion King. The warthog wasn’t very nice.” And we literally just stopped to look at an elephant. This is a very special transfer. STOP PRESS - our third moment of stickiness, this time it looks terminal for the first truck, one carrying bikes apparently. The road is blocked, so we’re going proper off-road to get around it. Shit’s about to get real…

Made it to camp, eight and a half hours later. Two trucks got stuck, and some adventurous travelers got out and walked the final 2 km. We had no idea we were that close. On the bright side, we got to see some giraffes on our detour. It appears the trucks that got stuck have our bikes and bags, well, Rob’s and mine anyway. So we’re just chilling, awaiting the race briefing, stress-free, soaking up the experience. The Migration Race hasn’t even started, and I already feel like we’ve been on an adventure. This is going to be good.

Day 2 - Stage 1 - MGR Basecamp to Maji Moto

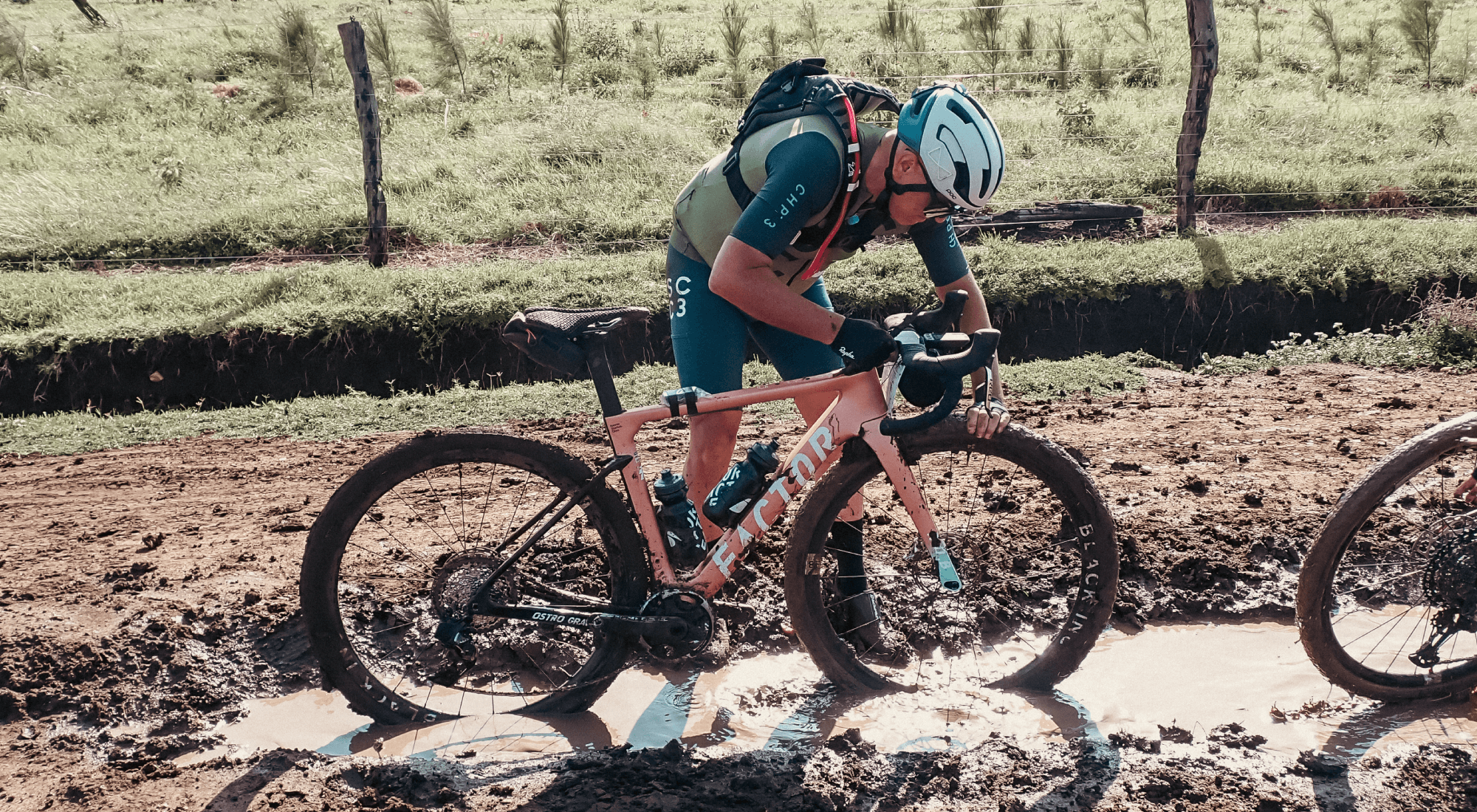

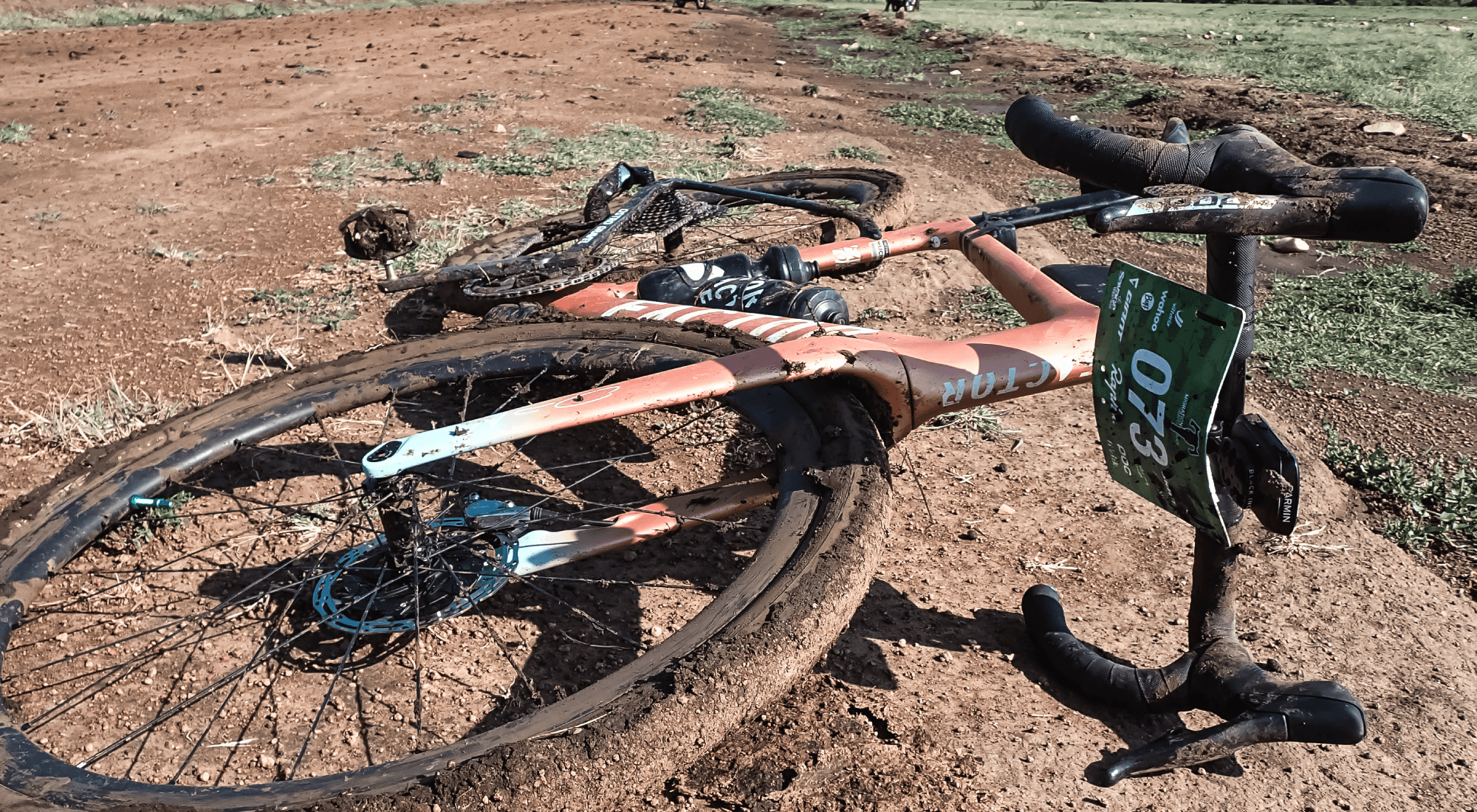

Will they run with the Leopards or the Zebras? For the first stage, which incidentally is Rob Gitelis’ first-ever gravel race, the competitors faced what sounds like apocalyptic conditions with an invasive amount of mud caking the bikes within the first hour of racing. “Harder than Unbound” sounds impressive, but does it sound fun? David Millar takes up the story from there:

Trial by Fire

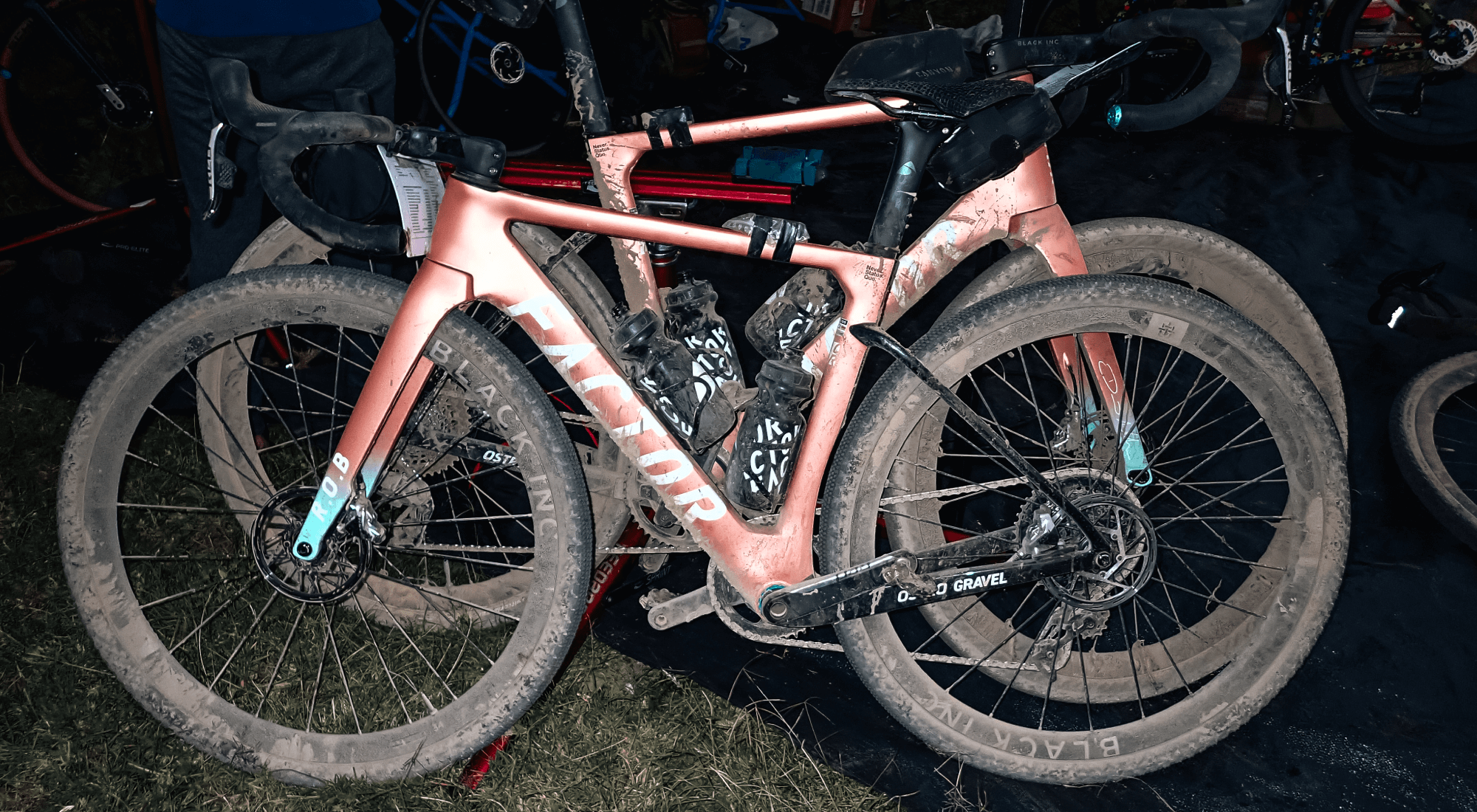

OH. MY. GOD. I’m sitting about 20m from the finish line with Rob, in some random fishing chairs, dazed and confused—can’t be bothered to go to the race meeting. We’ve asked Damian from POC to be our proxy. One of the officials just passed and asked how it was; we both just looked at him blankly. He told us the pros are saying it was way harder than Unbound, which, to be honest, barely flickered a reaction from us.

We couldn’t care less what the pros think; we know it was hard. He walked away when he saw our lack of engagement, and Rob said, “I didn’t find it enjoyable at all, not even a little bit.” This was Rob’s first gravel experience; it’s safe to say it was a baptism of fire. It took us two hours to do the first 16km. It was like the end of days. The first few kilometers of “gravel” were hardcore; there were punctures, crashes, water crossings, and then we hit the mud.

Not normal mud—this was trench warfare. Coming into it, things didn’t seem so bad. It looked like there were small passages we could make it through. This was not the case. Within meters of entering it, shit got real; everyone came grinding to a halt. The mud was like clay, tires were clogging and locking up, chains and chainrings were as useful as a chocolate fireguard. It quickly became clear that riding was no longer an option. Everyone stopped and tried to clean their bikes. At first, this was successful. People remounted, then tried again, and it got worse. There were bodies everywhere. Some persisted with trying to rid their bikes of mud, searching, begging for sticks. There weren’t many sticks available; they became a valuable commodity. No matter if you cleaned the bike, you couldn’t test it as there was mud as far as the eye could see. The only option was to hike-a-bike out of it.This then meant your shoes became clogs, and once you got out the other side, you were back to the stick-search-begging scenario. But first, you had to get out the other side. It became every man for himself. My buddy system with Rob disintegrated.

Testing the Buddy System

At last, I made it out, and it looked like I could get going again. Yet it took me a good 5 minutes of cleaning the chainring and my chain with my hand. Fortunately, I was wearing full-finger MTB gloves, thank you POC. The mud didn’t care about your frame clearance; it filled whatever gap was available. It was so ridiculous that I found it funny, just laughing to myself at how absurd it was. We had barely started, and we were all stopped. Finally, I made it out to freedom. Like breaking through a thick fog into sunlight, I hung around for Rob, not knowing where he was. Eventually, I found him standing in a puddle trying to clean his bike, adding to the comedy of it all. Welcome to gravel, Rob. It took me another 5-10 minutes to get Rob’s bike working again. I even took it for a ride to put a bucket load of power on the chain to get it to clean the mud out of itself. Amazingly, this worked. Then we were off again, and things didn’t really get better. I don’t think I’ve ever encountered such a hardcore route. At times, Cape Epic was bad, and for sure much worse at times, but the consistency of the horror today was second to none.

We finally made it to the first feed at 45 km. It took us three and a half hours to get there. Mikel, the man responsible for the Migration Race and Amani, was there, all smiles, loving it way too much. He told me how the leaders were already at km 90. Thanks, Mikel. Rob rolled in shortly after me. Our buddy system had involved me riding about 100m in front of him, willing him on. Not sure how that was helping his morale, but it helped mine. We got our drivetrains oiled, refilled our bottles, and set off again, but not before Mikel told us he was getting in the helicopter with the media guys to film us, so we better look good. I was psyched about this; Rob less so. Needless to say, they got shots of us with me approximately 100m in front of him.

Taking the Fork in the Road

Soon, we got to the turn-off point where you could choose to do the Zebra (shorter course) or Leopard (longer course). Rob made the wise move of taking the Zebra. I told him I was going to continue on the Leopard. He said meekly, “I understand.” I felt bad, but I gave the good news that I’d probably be arriving at the same time at the finish as him, which again, probably wasn’t so good for his morale. I then had some fun, until it wasn’t. There was one moment where I had champagne gravel and was fully in flow, only for a herd of cows to be blocking it when they literally had their pick of the Kenyan countryside. Speaking of cows, I saw hundreds of them today, and sheep, and some dogs. That was what Stage 1 Safari composed of, gutted.

I had the trails mostly to myself. I was quite a way behind everybody at this point. It was properly surreal, battering along them on my own in the wilds of Kenya with absolutely no clue where I was, totally dependent on my Garmin. There are no arrows or marshals here; it’s all self-guided from the supplied map. I got carried away at one point, barreling down a long fast (by today’s standard) gradual descent. It felt so good to feel like I was actually moving. I didn’t notice the left-hander coming up and came two-wheel sliding into it. By the grace of God, I managed to unclip and stamp my left foot down and somehow, miraculously, bounced myself back upright. I did it with such force that I twinged a muscle in my right thigh. I didn't care, though, as the relief and pride of staying upright were golden.

About 15 km from the finish, we turned onto a tarmac road, the first of the day. It was gorgeous. Like the whole day, it was a howling headwind, yet it was glorious. In the kilometers before, my internal monologue had been raging about how bumpy it was all the time. I was dreaming of a full-suspension bike and thinking about how I was going to tell everybody that was the bike we should be using.

Finally, I made it to the finish, and who was standing on the finish line having just finished? Rob Gitelis. Love it when a plan comes together. Tomorrow isn’t easier. Today was a slog, with a mere 800m of total climbing. Tomorrow is 166 km with 3000m of climbing. Rob is going full Zebra. I’m going Leopard.

Make sure to follow David Millar on Instagram for his latest race updates.

© 2026 Factor Bikes. All rights reserved / Privacy Policy |Terms