UPDATE ON ISN’S TEAM OSTRO

If you have been watching the racing in Europe recently, you may have noticed that Team Israel Start-Up Nation have moved back to racing on the O2 VAM and ONE, after being almost exclusively on the OSTRO VAM at the start of the season. For those interested and to alleviate any concerns for our riders, following our engineering team’s detailed analysis, we would like to take this opportunity to clarify what has happened and where the team OSTRO’s have gone.

What happened?

During the Omloop Het Nieuwsblad race, Tom Van Asbroeck encountered an issue with his bike which ended up with his steerer tube being broken inside the frame after striking a curb. He was able to avoid a major crash and got back on his spare OSTRO to support Sep Vanmarcke who finished third (also on his OSTRO), with Tom taking 18th after helping lead Sep out. The next day the team took to the start at Kuurne–Brussels–Kuurne on their OSTRO’s again, where Jenthe Biermans finished in 5th place. There were a number of question marks around Tom’s bike, including that it was the first time the frame had ever been ridden as Tom was on Covid protocol. However, out of an abundance of caution, Factor and the team jointly came to the decision that after the weekend’s racing we would put the riders back onto the ONE and O2 VAM for racing purposes until we could ascertain the exact root cause of the failure.

Analysis

At no point in our development and testing to date on either the OSTRO or the integrated O2 VAM, had we seen a failure of this type, including the 2020 Tour de France where riders like Andre Greipel rode the OSTRO. Therefore, it took some doing to ensure that we could repeatedly replicate the failure in a controlled environment, and then assess what the root cause of it was. Impact followed by fatigue tests are relatively common in the industry (ISO has the reverse steerer impact followed by fatigue and a steerer torque test for example) but in this case, we were a bit flummoxed as the steerer system had passed our internal standards which go well above these minimums with no issues.

Once we had the fork in question back into our possession, the first thing we observed was that the failure had occurred adjacent to the bottom of the compression plug. We started looking at this area and system for the potential cause of the failure. The failure location was highly unusual in and of itself, with the team riders being in the ‘slammed’ position it meant that part of the steerer was a fair way into the head tube. Typically failures in steerer tubes will manifest themselves at the split ring location where the reaction force from the bearings is concentrated in a small area of the steerer tube by the aluminium centering ring. An immediate tell was that the failure happened almost exactly at the bottom of the compression plug so we started looking into this with the team.

It turns out there were quite a few struggles with maintaining headset preload during the early 2021 season with the OSTRO. However, we hadn’t seen this during the team’s use in the 2020 races, which then had us looking at the changes we’d made to the bike between the seasons. In the transition between the 2020 and 2021 season, we put the OSTRO in full production, with the team having ridden relatively pre-production bikes in the 2020 Tour (for example, they had Press Fit BB’s, not T47) and we made a number of changes based on this racing experience. These changes included thickening and changing the steerer tube inner profile for better mass production stability and fit with the compression plug, as well as putting the compression plug into full mass production vs CNC’d.

Understanding how the team was using the fork, as well as what various solutions to issues and any other problems experienced by the team mechanics formed the basis for our design of experiments to replicate the failure shown in use. We prescribed a number of stiffness (static mass displacement) tests, fatigue tests (repeated load tests) and impact tests to try to uncover the root of the issue, and after many individual and combined tests, we were finally able to simulate it.

Internal Impact Testing

We began by impacting the steerer tube similarly to what would happen in a crash or a strange impact (think bike falling over, slamming a pothole, curb, etc), then we would fatigue that same steerer at progressively higher levels of force. What we found was that when the push-down fatigue level was raised high enough (approx. 160kg gross load where the shifters are mounted) we were able to simulate the team’s preload issues with it gradually coming loose. Our test technician would then stop the test, retighten the headset at a progressively higher and higher torque level and then continue to cycle the fork. Eventually, we had it, a simulation of failure seen in use by Tom, and we could begin to understand the fundamental issue behind it.

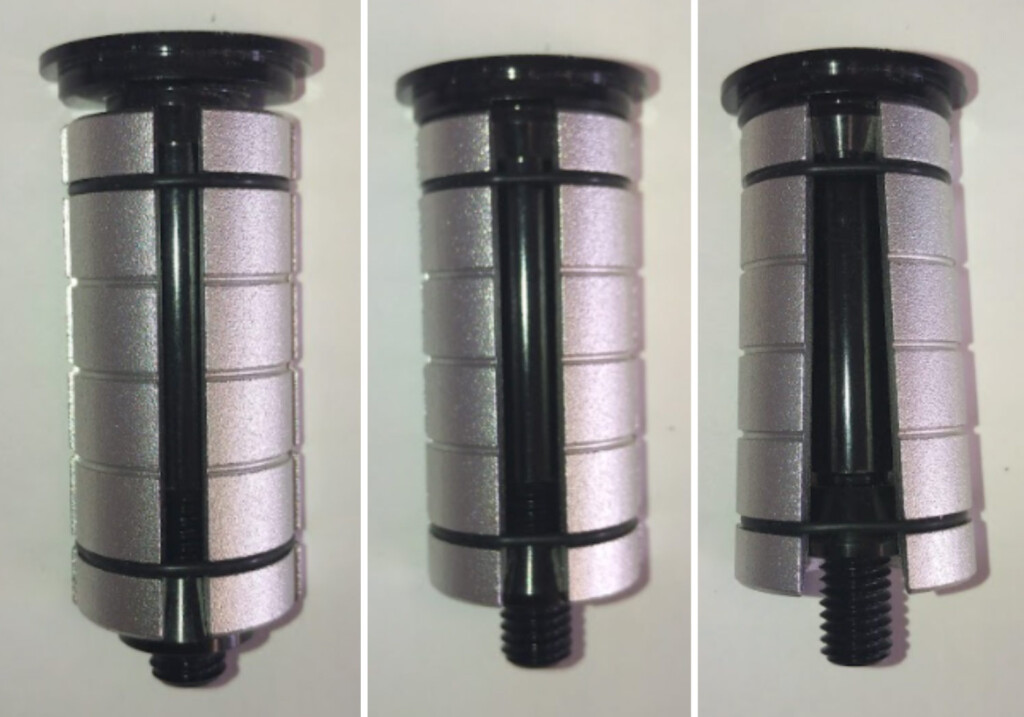

In pursuit of the root cause of this preload loosening, we came to understand that the issue was the product of multiple smaller issues stacking up into a major potential problem. At its root, the primary issue the team was having was the struggle keeping preload on the headset during cobbled races, the preload issue did not manifest itself in the smoother UAE tour for example. During development, the retention force of the preload force generated by the compression plug was benchmarked relative to a conventional round steerer plug with both pulling loose at about 400kg. On review of the parts the team had on hand, we found that the preload provided by their compression plug was lower than we expected. After looking at the part carefully, we determined there was a batch issue with the plug provided to the team. A batch of them received a clear anodizing treatment AFTER sandblasting which then decreased the surface roughness and ultimately the pull out strength. You can see the difference in the finishes below, with the plug on the right showing a ‘white metal’ finish, with a high degree of roughness.

This pointed to the cause of the preload issue, but it did not help with why the failure occurred when the headset worked its way loose and was retightend. The root cause of this was a bit harder to find, but ultimately it’s quite clear when you look at the parts in use. Recalling that the failures happened after a progressive tightening of the plug with time, we can look at what happens to the plug as we increase the number of engaged threads:

This behaviour of the plug was not as designed and on investigation, it was quickly realized why; the taper length of the upper expansion wedge did not conform with the original plugs used by the team the year before, or with previous batches, something had changed.

This addition of a flat surface or step on the top of the taper allowed the upper part of the silver friction surface to bottom out on the top wedge prior to the lower wedge, thus fully concentrating the preload resisting force entirely at the bottom of the preload plug. This decreased the amount of area subjected to friction on the inside of the steerer, and caused further loosening of the headset, resulting in the further tightening of the plug, causing further concentration of this force. This was corroborated by the team mechanics complaint that eventually the lower nut would just spin, without tightening further. This is because eventually, the lower expansion wedge would bottom out on the bolt, meaning that the lower part of the steerer tube was seeing a tremendous amount of distortion in that small local area.

Conclusions

At last, we had our smoking gun, lack of preload led to overtightening which coupled with a batch issue on the upper wedge led to non-uniform engagement of the compression plug on the wall. This led to local deformation in the steerer that manifested itself as a failure under post-impact fatigue where the compression plug terminated in the fork.

The solution is pretty simple, don’t over tighten your compression plug. If you find yourself in search of greater preload retention strength, then we can supply a compression plug with the proper roughness, coupled with a turning operation on the upper taper to match the engagement length and angle of the lower, giving both greater preload tightness, and ensuring uniform distribution of preload force.

Unfortunately, simple solutions are rare in the World Tour and we had two major issues complicating the resolution for the team. First was uncertainty about which forks were from the preproduction Tour de France batch and which were from mass production, and which bikes they lived in; the second being that in the pursuit of preload security, the team eventually permanently bonded in the compression plugs on virtually all frames, using 2 part thermoset epoxy, and being diligent they also tightened these up at the same time.

This has rendered it impossible to sort which forks are which, so we’re in the process of replacing all of the forks. Once the replacements have been supplied to the team the OSTRO will be racing again. We’ve also taken the opportunity to further ‘fool proof’ the system, with a bonded threaded preload device, which will add weight and maybe a source of headache for regular riders but for the team is ideal.

What does this mean for you, the rider?

We have had limited reports of Factor riders struggling with preload but for anyone that does report this we are supplying the replacement plug to them immediately via their shops, distributors or directly. However, at its root if there’s no preload issues there should be no overtightening, which will avoid any further issues.

This all being said, there are many bikes happily in use without any preload problems, as the batches prior to this troublesome one followed the original drawings. If you find yourself unable to keep preload on the headset of your OSTRO or VAM, please contact Factor for a replacement compression plug, but do not attempt to resolve the issue with overtorque.

If you have any questions or for more information, please contact our team.

LATEST NEWS…

© 2026 Factor Bikes. All rights reserved / Privacy Policy |Terms